Report on the 2022 nesting of the White-bellied Sea-Eagles

Introduction:

There has been a Sea-Eagle nest in the Newington Nature Reserve at Sydney Olympic Park by the Parramatta River for many years, with a succession of eagle pairs renovating a nest in the breeding season. As in previous years since 2009, the breeding relationships, behaviour and diet of the White-bellied Sea-Eagles were studied using video CCTV cameras by night and day and by limited physical observation during daylight hours, from the time of nest renovation to fledging and beyond where possible. In early 2022 a new Research Proposal was submitted and all approvals gained.

Stephen Debus, in his study of Sea-Eagles breeding in Northern Inland NSW, noted that it has been assumed from previous observations that there is a strong division of labour, during the breeding season, with the female said to perform most of the nest-based parental behaviour and the male most of the hunting. (Cupper & Cupper 1981; Hollands 1984; Marchant ∧ Higgins 1993; Olsen 1995, 1999).Debus, S.J.S. Biology and Diet of the White-bellied Sea-Eagle Haliaeetus leucogaster Breeding in Northern Inland New South Wales Australian Field Ornithology 2008, 25, 165–193.

Our study has revealed a less obvious division of labour, with the male showing more of the “caring roles” than was believed. Both share nest renovation, incubation and brooding, as well as feeding the young, though the female spent more time with the eggs and young, with the male bringing more of the prey.

This study has observed a disturbed and shorter post- fledging period of dependence, reported as 2-3 months by others (Debus 2019). This has appeared to be mainly caused by disturbance in the forest and in nearby industrial and urban areas. This is affecting the survival of fledglings from this nest.

Summary:

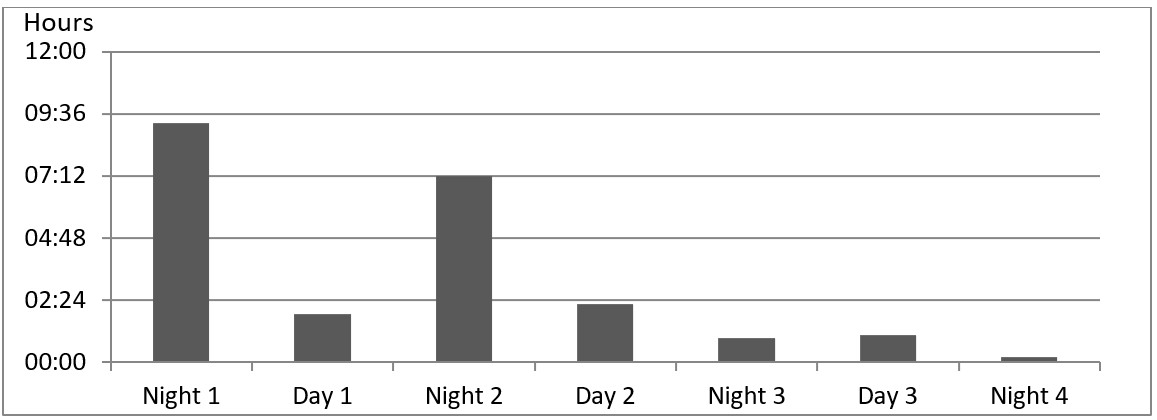

Both eagles contributed to nest renovation and shared incubation, though the female alone incubated at night. Incubation was again around 40 days. This study again reported delayed incubation of the first egg, resulting in a “catch up” at hatch. The eggs were laid nearly 80 hours apart and hatched just under 41 hours apart.

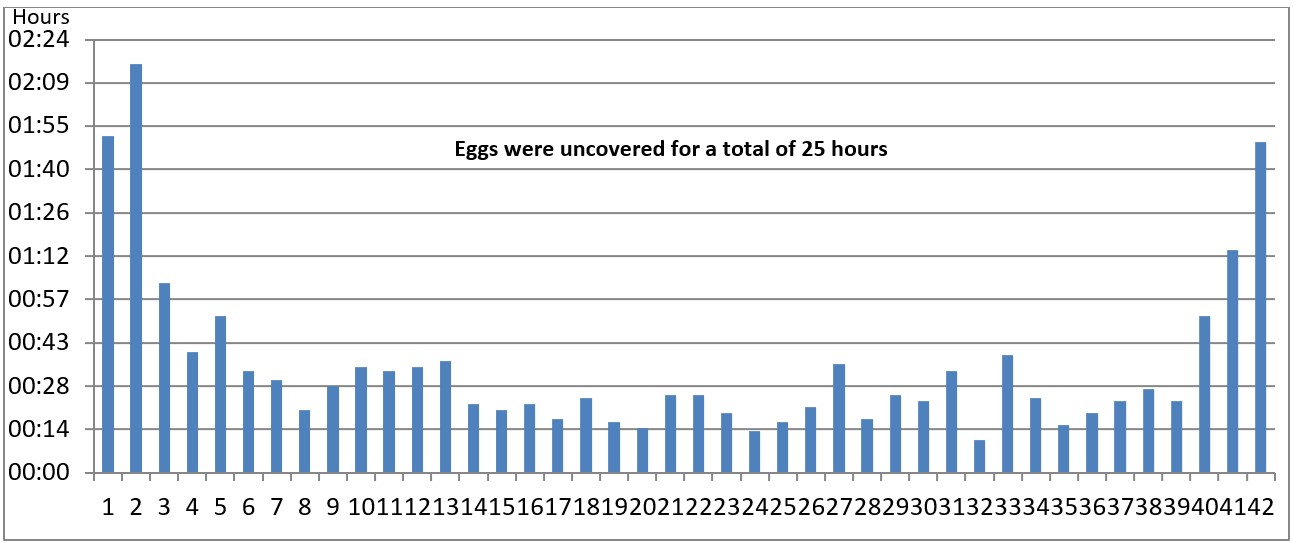

From lay of the first egg to hatch of the second egg on day 42, by day the female incubated for 284 hours and the male for 195 hours. The female alone incubated at night. The eggs were uncovered for a total of around 25 hours from lay of the first egg to hatch of the second.

Both eagles again shared daytime brood duty of the nestlings, though the female was in attendance for longer and again she alone brooded at night. There was no serious sibling rivalry though at times the younger was more submissive when food was delivered. Later at times both grabbed food first and mantled over their catch. Both adults brought food and fed the nestlings, though the female fed more often and the male brought most prey. As the nestlings grew and developed their feathers, brooding time decreased. More prey was brought for the hungry nestlings and they began to self-feed, but were still dependent on prey the adults brought.

The older nestling SE29 branched at 73 days from hatch and fledged at 77 days. SE30 branched at 75 days from hatch and fledged at 82 days. The nestling period is reported as 81-84 days (Debus 2019).

The post-fledging period has again proved to be of concern at this study area and both young birds left the area very soon after fledging. The post-fledging period of dependence is reported as 2-3 months (Debus 2019) when the young birds would be expected to remain in the nest area, with the parents delivering food. They would develop experience in hunting and survival, before dispersing further afield. It is considered that disturbance in the surrounding residential and industrial area as well as constant harassment by other birds contributed to their premature dispersal from the nest area.

In spite of extensive wetlands nearby which would give the young birds shelter, both very soon were not seen near the nest, no feeding was observed and both eventually were captured and taken for veterinary care. The injured older bird SE29, despite surgery and care, was eventually euthanised. His injured foot would have prevented him from functioning as a raptor and he would have been in constant pain. The younger SE30 is in the Raptor Recovery Australia rehabilitation facility and hopefully will be fitted with a satellite tracker, enabling his dispersal to be followed (as for SE27 from the previous year).

Nest Renovation 2022:

The eagles again used the nest from the previous year, in a tall Grey Ironbark Eucalyptus paniculata. The first sticks were brought in March, with both eagles bringing sticks and building up the rim of the nest again. Just before the first egg was laid, the male had brought 277 sticks or leaves and the female 249.

As renovation progressed, lots of green leaves were seen lining the nest. The male was the prey provider at the nest during renovation, bringing 19 fish of different kinds and 1 bird carcass. Mating often followed their early morning duets or when prey offerings were brought to the nest.

Incubation period:

The First egg SE-29 was laid on June 8, 2022, at 17:37 (5:37 pm).

The eagles again delayed incubation after this first egg was laid –the egg was not incubated for around 9h15m total on the first cold night after lay. The female incubated on and off, with brief breaks to stretch and roll the egg until 11pm. It was then uncovered until the male came to the nest and started his first shift in the early morning. The egg was only incubated on that first night for a total of 2h 45m. She slept on the nest or a branch when she was not incubating and he was also on the nest tree nearby.

On the second night after the first egg was laid, the female alone incubated for a short time, leaving the egg uncovered for 7h14m. As we have seen in previous years, as lay of the second egg is expected, she increased the incubation time. On the third night since lay, she only left the egg uncovered for just under an hour. She incubated for the rest of the night, with short breaks for stretching and rolling the egg. Both adults were on the nest tree at night. Both incubated by day, though the female incubated for longer.

The second egg SE-30 was laid on June 12, 2022, at 01:12 (1:12 am).

The female had a restless night, but was sitting tight in the cold. The eggs were laid 79 hours 35 min. apart, similar to last year.

Early morning, the male began with a few soft calls, then called the female off the eggs to a nearby branch, with a duet and mating, reinforcing their bond. He then took his first incubation shift at 06:27, while she took a well-earned break. Full incubation began then, with 2 eggs laid. Incubation continued, with both sharing daytime shifts and the female alone at night.

Changeovers during the day showed a typical pattern, with the female reluctant to get off the eggs. When the male was incubating by contrast, he typically backed straight off the eggs as she landed.

From lay of the first egg to day 42, hatch of the second egg, during the day the female incubated for 284 hours and the male for 195 hours. The eggs were uncovered for a total of around 25 hours.

The female alone incubated at night, covering the eggs for the whole night with brief breaks to stretch or roll the eggs.

The male however brought in the prey to the nest, though both eagles probably fed themselves down on the river.

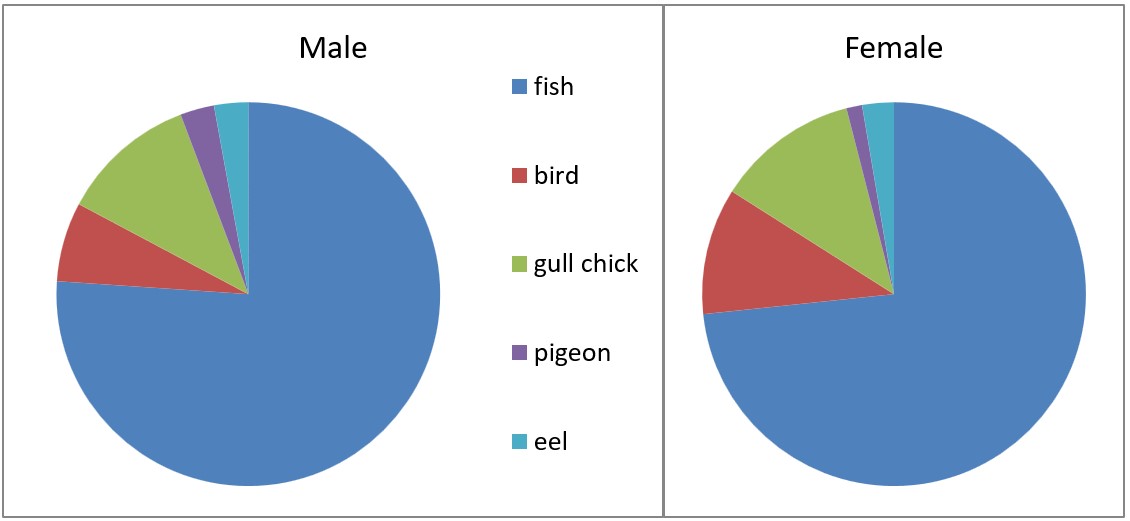

During the incubation period the male brought in 31 prey items - 25 fish, 3 birds, eel, a rat or similar and something unknown. Lady brought 1 fish.

Hatching period:

Pip on the first egg was seen on July 17, the 39th day since the first egg was laid. “Pip” is a bulge in the shell and then a small crack, as the little chick begins to break free from the shell. The chick was probably working inside the egg earlier in the night. The female was very restless on the cold windy night, up and down off the eggs and hearing SE29 cheeping. She had a brief break early in the morning, after duetting from the male nearby. He incubated for well over an hour. Both were restless, up and down rolling the eggs. The little beak was visible moving in the pip hole. The first chick SE29 was clearly seen out of the shell at 14:26 on July 18. It had been a long wet time for the female, shuffling and shifting as the chick struggled to hatch out of the shell. SE29 hatching time was 39 days and 21 hours. The second egg also pipped that day.

SE29 received its first tiny feed the next day and was fed by the female 8 times during the day with prey brought by the male.

The second chick SE30 was first clearly seen out of the shell at 7:06 on July 20. SE30 hatching time was over 38 days and 6 hours. It received its first tiny feed later in that day.

The 2 eggs were laid just under 79h 35m apart and hatched 40h 40m apart – indicating a catch-up after the delayed incubation of the first egg.

Feeding during the nestling period:

Initially the female fed the chicks, though later both parents fed the young ones. The female contributed more feeds in total than the male.

There was little sibling rivalry, though as expected SE29 the first hatched and larger chick usually received the first feed, often after pecking its sibling a little. SE30 often turned aside in a submissive posture in the first few weeks when food was delivered. By day 31 since hatch, SE29 was usually getting fed first, as the younger SE30 turned aside, though both were getting fed. As both grew, by day 46, SE30 was also mantling over food and snatching it from the parents.

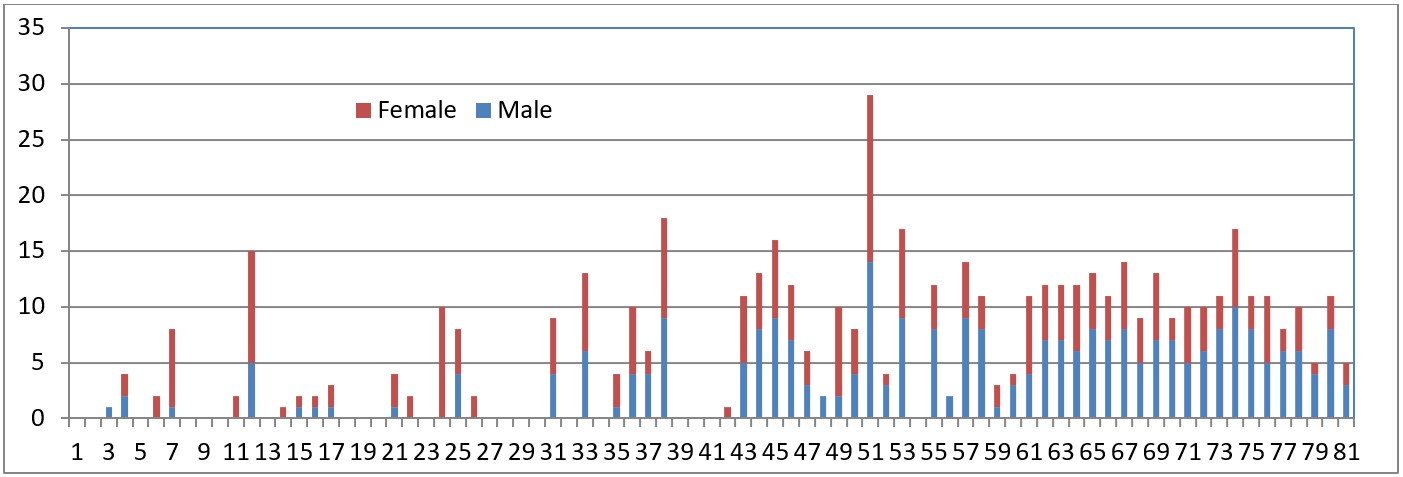

Initially as the nestlings grew, the number of feeds increased. By 44 days since SE29's first feed, the female had fed 260 times and the male 38.

Again the male brought more prey - 122 offerings to her 30. As the nestlings grew, the female also brought in more prey to satisfy them.

By day 48 from hatch, both nestlings were growing and developing well, with little aggression. The nestlings were fed less often as they grew stronger and started to self-feed from prey the parents left on the nest. Both were seen mantling over prey brought in. At 58 days from the first hatch, both were grabbing prey from the adults and self-feeding. Both were also fed by the adults at times.

Prey during Nestling Period:

Both the male and female brought mainly fish, including bream, whiting and leatherjacket. From around week 40 from hatch, both also brought gull chicks to the nest sometimes still alive. Many Silver Gulls were nesting on the wrecks in Homebush Bay the gulls may have been more plentiful or such prey was beneficial for the stage of nestling growth.

For the full nestling period, from hatch of SE29 until both left the nest on October 10, the female fed the young 358 times and the male 50 times.

In that same period, the male brought 209 prey items to the nest and the female brought 75. (see appendix for examples of prey species). Both mainly brought fish prey.

Initially the chicks were brooded and guarded almost constantly. As the chicks grew stronger and developed feathers, brooding time decreased with the adults spending longer away each day, leaving the chicks alone uncovered on the nest.

By 2 weeks from hatch, fluffy feathers were starting to show and by around 3 weeks, pin feathers starting to appear.

By 18 days since SE29 hatched, the female slept beside them at night for over 2 hours. The nestlings were left alone all night for the first time on the 45th day from hatch of SE29, with the female sleeping on a branch nearby.

At 5 weeks , they were almost equal in size and both were standing more. Both were flapping their growing wings and beginning to hop on the nest. At 7 weeks, both were flapping and jumping vigorously on the nest. With feathers for warmth and developing strength, they were left alone by both day and night.

Branch and Fledge period:

The nestling period is reported as 81-84 days (Debus 2019 ).

As they grew, both nestlings were seen flapping and jumping on the nest developing strength and skills. The older nestling SE29 was seen walking up a branch a way and then spending a little time near the nest.

SE29 branched at 73 days from hatch. After branching, SE29 continued to self-feed on the nest with his sibling and to flap and jump there, gaining strength and power. Last year SE28 branched at 77 days from hatch and SE27 at 81 days.

SE29 then fledged at 77 days, flying below the nest and then returning after spending some time on nearby branches.

SE30 branched on the same day, rather cautiously, at 75 days from hatch. Initially both young fledglings were observed on the nest and nearby branches, self-feeding and exercising.

During this time the nest and eagles were persistently swooped by both Australian Magpies and Pied Currawongs. This swooping may contribute to the fledglings’ reluctance to stay around the nest and may hasten their leaving the nest area.

SE29 was observed to fly a short way from the nest, sleeping on a branch near the nest at 80 days, even though it was raining. The following day he ventured further, but returned to the nest when the male brought prey in – a juvenile gull. This was his last observed feed.

The following day however SE29 was not seen at the nest and the next day was reported in a nearby residential area, swooped and chased by both magpies and currawongs. He was seen to crash into a building and fall to the ground. He was captured and held until he was taken by a WIRES carer to a veterinary facility for assessment and care. He then was cared for at the Raptor Recovery Australia facility.

SE30 was more cautious and fledged at 82 days from hatching. He returned to the nest again after being swooped by currawongs. SE30 was self-feeding well on the nest or nearby branches.

Then however, serious swooping by both magpie and currawong neighbours caused SE30 to take flight.

At the end of day SE30 had not returned to the nest. The next day after hearing the alarm calls of other birds, SE30 was found on the ground nearby in the forest. We watched for some time, then gently urged him towards the nest area. He appeared unhurt, could walk or hop and could fly, though not reaching any height. We left him on the ground closer to the nest. Later other watchers in our team heard and saw him closer to the river. He must have flown over the forest fence and across the wetlands to reach that area.

Over the next days, SE30 was heard and seen in the Nature Reserve wetlands though he was not observed being fed by the adults, although they brought prey to the nest. SE30 was then seen in nearby residential areas, on verandas and flat roofs, in suburban backyards and leafy trees in the surrounding areas. Some of our eagle watchers reported sightings and we were able to monitor his progress, without intervention.

As required by the approved Intervention Policy, the team only observed that the young bird was safe and monitored his location and condition. Finally on the 11th day since fledging, as he appeared unable to leave, SE30 was captured on the ground and taken to Taronga Wildlife Hospital for care. Then he was taken to RRA for care and rehabilitation.

Basically then, neither young eagle remained in the nest area after fledging as would be expected. Neither was seen to be fed or guarded by the adults. Both adults were seen to bring prey to the nest, then taking it away again. It is considered that disturbance in the surrounding residential and industrial area as well as constant harassment by other birds contributed to their premature dispersal and for both to be “lost”.

Both then remained in care. SE29 when taken into care was found to have suffered internal trauma and a fracture just above his foot. Despite orthopaedic repair, this injury did not heal sufficiently for the young bird to be released and euthanasia was recommended (see appendix for report from RRA).

SE30 remains in care and rehabilitation at RRA and it is hoped that when considered strong enough, he will be fitted with a satellite tracker as part of the research project of Australian Raptor Care and Conservation Inc. A juvenile SE27 from the previous year 2021 was also part of this tracking program. This tracking has revealed how far these juvenile eagles wander. It is hoped that SE30 will be released in a similar approved area during the normal time of dispersal – before the end of February -March. It is considered that release in the natal urban area on the Parramatta River is not recommended after the post-fledge disturbance of this and previous seasons.

The 2022 breeding season monitoring has again revealed valuable information on this Vulnerable species and indicates the problems of urban-breeding Sea-eagles.

Thanks go to all of the EagleCAM team: camera operators, the moderators and our followers; to Sydney Olympic Park Authority and National Parks and Wildlife; to Taronga Wildlife Hospital, Raptor Recovery Australia and Australian Raptor Care and Conservation Inc.

Notes on treatment of SE29 at Raptor Recovery Australia:

_______________________________________________

As you know SE29 was rescued in early October, after some sort of severe trauma (we are not sure if he flew into a window or was hit by a car).

When he arrived he was bleeding from inside the beak indicating a bleed in the lung following the trauma. He also suffered a particularly nasty fracture just above the foot, which you can see in the radiograph attached to this post. The challenge about this fracture is firstly, that it is quite oblique, and secondly, that it is very far down in the bone, making the orthopaedic repair required quite difficult.

While stabilising and after consultation with many other raptor veterinarians around the world, we initially tried to stabilise the foot in a special cast. But it became apparent quite soon that due to the oblique nature of the fracture the fragments just could not be immobilised properly and there was still some sliding.

Normally these fractures in birds are repaired with an external fixation device. This involves crossbars through the bone which are connected and held in position by external rods. The goal is to have two crossbars in each fragment of the bone. We knew that trying to repair this fracture would be a push, because of the little room left for us in the fragment closer to the foot.

But SE29 was a young bird (this helps with healing) and he was dealing well with the process of being in care, having a generally gentle demeanour, so repair was attempted) and we placed a type 2 external fixation device. You can see on the picture what this structure looks like.

We then had to wait for the bone to mend until we could remove the pins. During this whole process SE29 has been a gentle, strong bird and has allowed us to take him through the rehabilitation process.

However, we have promised ourselves, we would only persevere with his rehabilitation if there was a reasonable chance for SE29 to return into the wild. This is where he came from, and the life of freedom is what he should have if we could make it so.

Two months into the rehabilitation process, the external fixation device was removed and it became clear that some of the tendons making the digits move did not work normally any more, and possibly there was some joint damage at the tarsometatarsal - phalanx 1 joint.

The foot is a structure a raptor just cannot live without, and we had to accept that our attempts had not worked out as we hoped. We knew it was a push from the start (again, this was a very unfavourable fracture), but SE29 had just been doing so well until then and he made us hope even more it would work out in the end. Unfortunately at this point it became clear, SE29 would not be able to be released and he was euthanased for the reasons described above.

Much like all of you, who fell in love with this little bird from since he was an egg, working with him and getting to know him also allowed him to take a very special place in our hearts and sharing these news fills us with sadness. But we are glad that we did give this bird a chance, because otherwise we would have never known.

Acknowledgements:

The EagleCAM research project team acknowledges the assistance of National Parks & Wildlife Service and Sydney Olympic Park Authority in approving this research and facilitating access to the Nature Reserve and other facilities.

We acknowledge the essential assistance from the EagleCAM team:

Camera installation, electrics, cabling and maintenance: Judy Harrington, Geoff Hutchinson, Bob Oomen and Chris Bruce

Daily Operations & Socials: Shirley McGregor

Minnit Chat: Helen Stibbs

Research Notetakers: Dasha, Cathy, Kathryn, Pat and Helen

Camera Operations: Dasha, Cathy and Helen

Additionally, we also have a wonderful team of volunteers including Facebook admins, chat moderators, ground observers and more (too many to mention here). Above all, thank you to our Supporters, for funding this project.