Report on the 2021 nesting of the White-bellied Sea-Eagles

Introduction:

There has been a Sea-Eagle nest in the Newington Nature Reserve at Sydney Olympic Park by the Parramatta River for many years, with a succession of eagle pairs renovating a nest in the breeding season. As in previous years since 2009, the breeding relationships, behaviour and diet of the White-bellied Sea-Eagles were studied using video CCTV cameras and by limited physical observation during daylight hours, from the time of nest renovation to fledging and beyond where possible. In early 2021 a new Research Proposal was submitted and all approvals gained. .

Summary:

The breeding pair of eagles renovated the nest used the previous year.

The first egg was laid on June 19. The eagles again delayed incubation until the second egg was laid on June 22. Incubation has been observed in our study to be around 40 days and the first egg hatched 39 days from the lay of the second, after full incubation began. The eggs were laid 80 hours apart and were hatched just over 49 hours apart.

Stephen Debus, in his study of Sea-Eagles breeding in Northern Inland NSW, noted that it has been assumed that there is a strong division of labour, during the breeding season, with the female said to perform most of the nest-based parental behaviour and the male most of the hunting.

Our study has revealed a less obvious division of labour, with the male showing more of the “caring roles” than was believed. Both eagles contributed to nest renovation and shared incubation, though the female alone incubated at night. Both eagles again shared daytime brood duty, though the female was in attendance for longer and she alone brooded the nestlings at night. There was a short period of sibling rivalry at around 4 weeks from hatch. Both adults brought food and fed the nestlings, though the female fed more often and the male brought most prey.

The younger eaglet SE28 branched at 77 days from hatch and SE27 branched at 81 days a few days later. Both eaglets fledged on the same day. SE28 fledged at 83 days and SE27 at 85 days from hatch. After fledging, neither eaglet returned to the nest nor were seen being fed by the adults. SE28 has not been seen in the area and its survival is not confirmed. SE27 was taken into care at Taronga Wildlife Hospital, after being found in a weak state. She was released, then after another session in care, was taken to Raptor Care Australia for rehabilitation. To monitor her progress after her eventual release, SE27 was fitted with a tail-mounted solar-powered satellite tracker by ARCC Inc

Nest Renovation 2021:

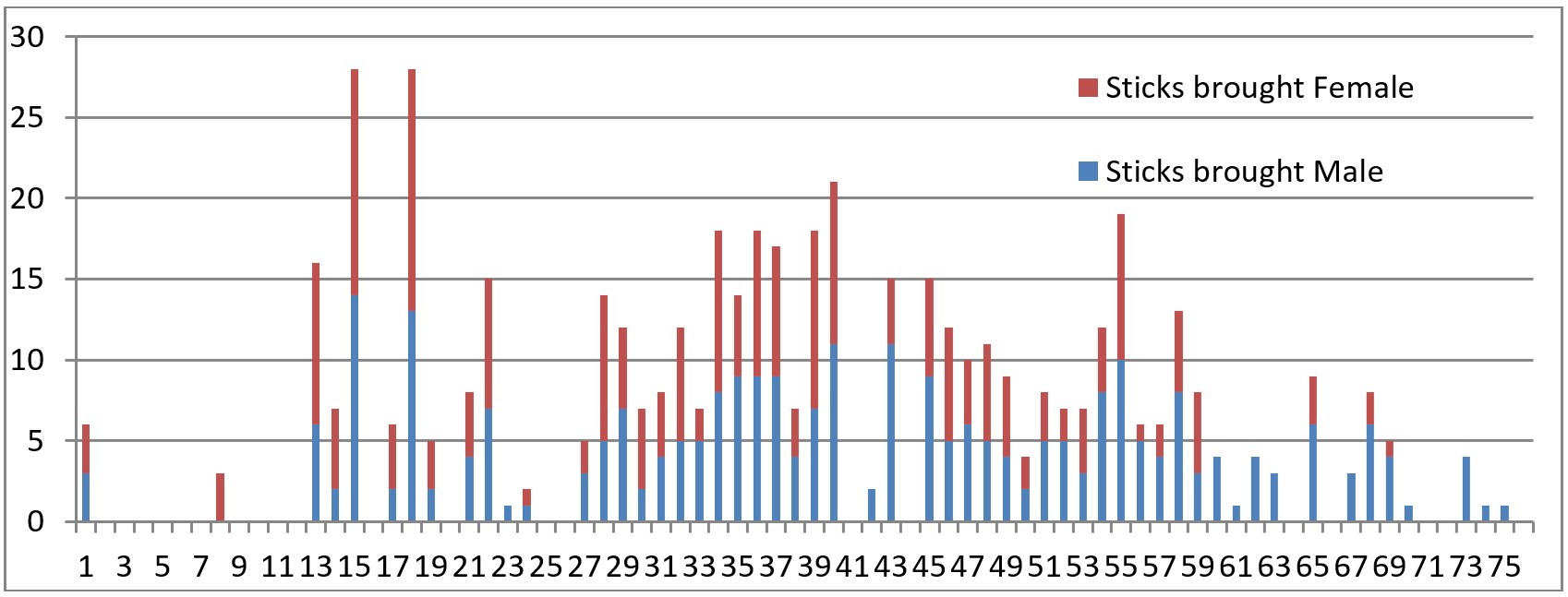

The first sticks were brought to the nest used the previous year on March 26. During the renovation period, from April 12 to the lay of the first egg, the male brought 276 sticks or leaves and the female 235. Both arranged their offerings and continued to re-arrange sticks and leaves to line the nest at other times.

Prey provisioning during renovation:

The male brought more prey items to the nest, bringing 34 offerings, while the female brought 3. Most prey was fish, with a few birds and an eel, plus leftovers from other meals. Both would have caught and eaten prey elsewhere, on the river or further away.

Mating:

Mating was observed from the cameras on or near the nest, frequently associated with the morning duetting chorus.

Egg lay:

The first egg was seen at 17:45 on June 19, though probably laid at around 17:28. A cold and windy night followed, though the eagles left the egg uncovered for some time, as expected from our previous observations of delayed incubation.

The second egg was laid at around 01:18 on June 22, with the first view around 5 minutes later at 01:23. The eggs were laid some 80 hours apart.

Delayed Incubation:

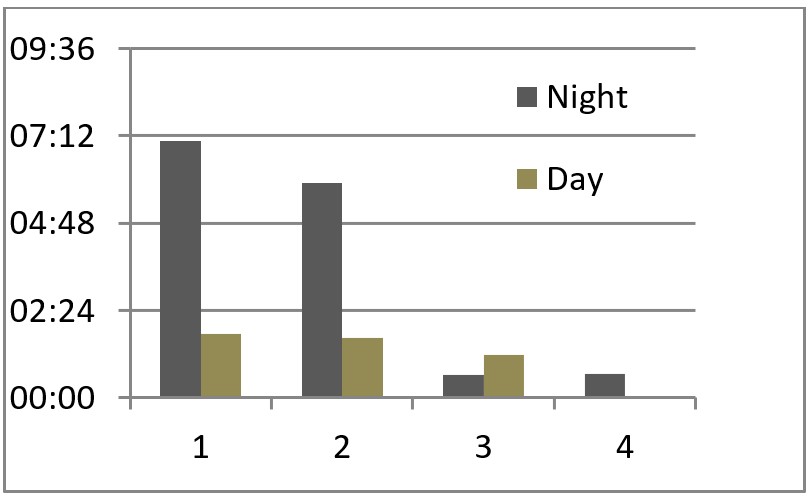

After laying in the early evening, the first egg was left uncovered for just over 7 hours on the first night. It was very cold being a June night. Egg 1 was uncovered over 14 hours total at night and 4.5 hours by day before egg 2 was laid. The first egg was left completely unattended on the nest for nearly an hour total during this initial period, with both eagles away from the nest.

Egg 1 was uncovered over 14 hours total at night and 4.5 hours by day before egg 2 was laid.

Eggs were laid around 80 hours apart.

The male also incubated on the first night and then the female alone on following nights.

As the lay of the second egg approached, the time the egg was uncovered decreased.

Egg 1 was laid on June 19 at 17:28 SE-27

Egg 2 was laid on June 23 at 01:18 SE-28

Eggs were laid around 80 hours apart

As the lay of the second egg approached, incubation time increased, particularly at night.

| Between Eggs | Female Incubating | Male Incubating | Eggs Uncovered | Nest Unattended |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Night 1 | 3:03 hrs/min | 1:52 hrs/min | 7:04 hrs/min | ~ |

| Day 1 | 3:12 hrs/min | 6:51 hrs/min | 1:45 hrs/min | 0:26 hrs/min |

| Night 2 | 6:05 hrs/min | 0:00 hrs/min | 5:55 hrs/min | ~ |

| Day 2 | 4:46 hrs/min | 5:34 hrs/min | 1:38 hrs/min | 0:31 hrs/min |

| Night 3 | 11:23 hrs/min | 0:00 hrs/min | 0:38 hrs/min | ~ |

| Day 3 | 5:34 hrs/min | 5:15 hrs/min | 1:11 hrs/min | ~ |

| Night 4 | 11:25 hrs/min | 0:00 hrs/min | 0:40 hrs/min | ~ |

| Total | 45:28 hrs/min | 19:32 hrs/min | 18:51 hrs/min | 0:57 hrs/min |

Incubation:

Incubation has been observed to be around 40 days and the first egg hatched 39 days from the lay of the second, after full incubation began.

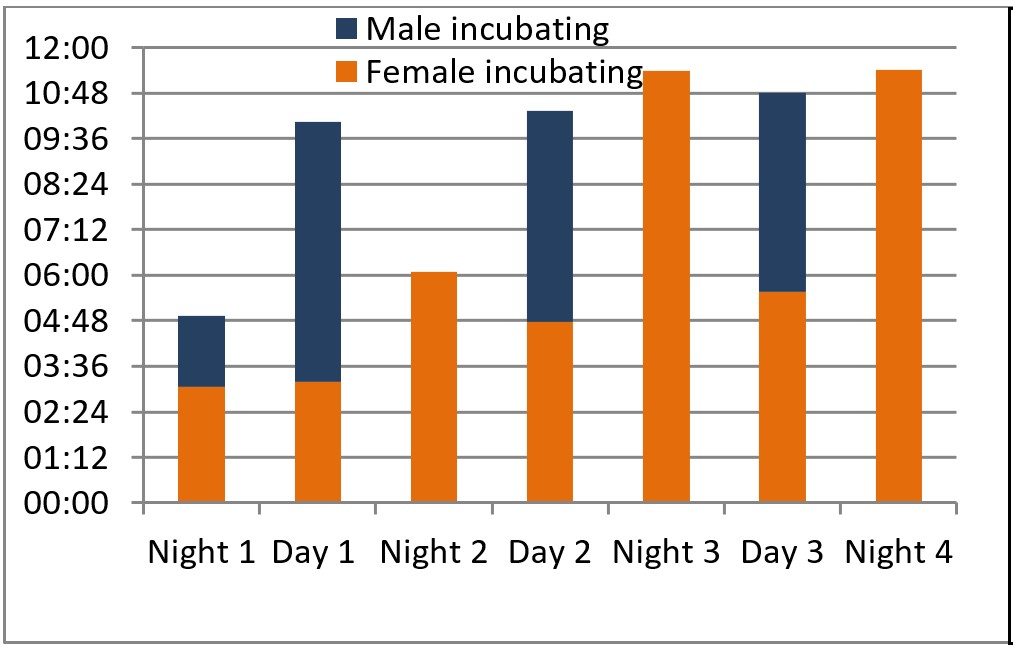

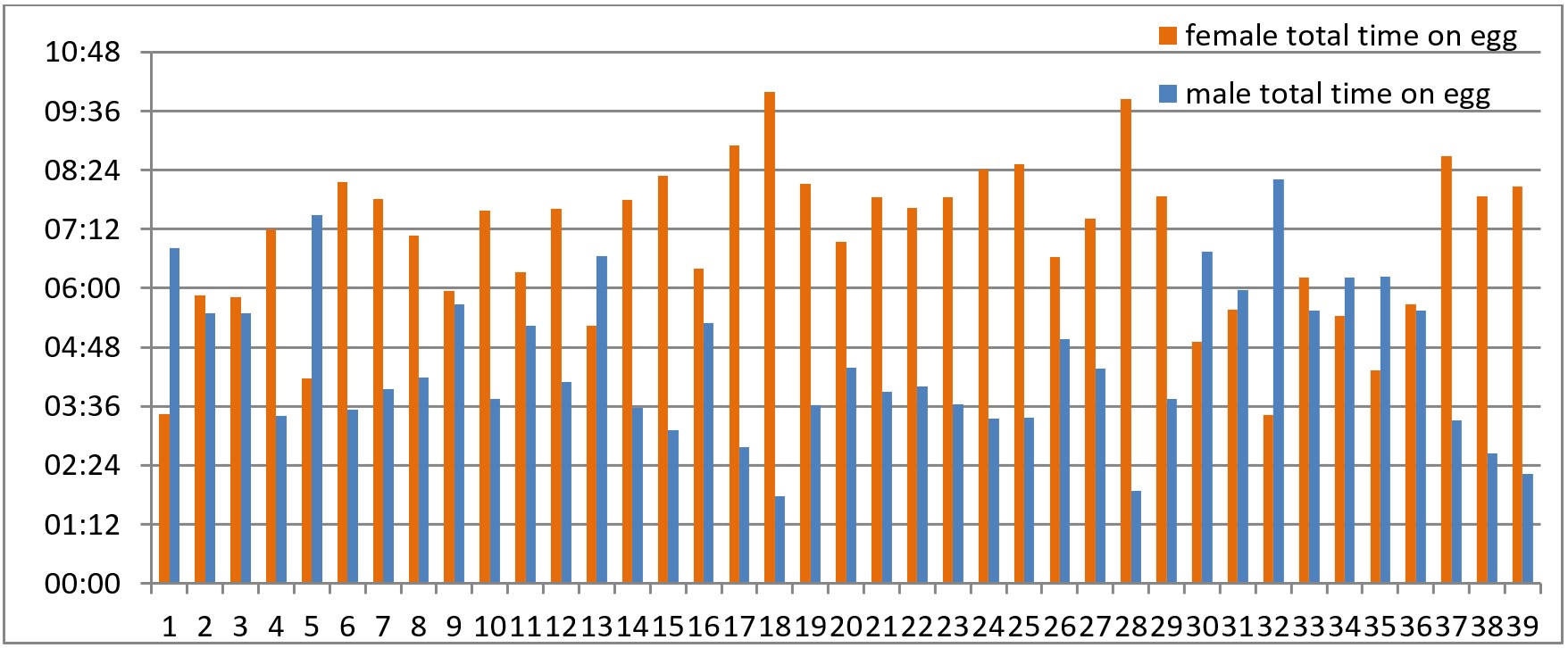

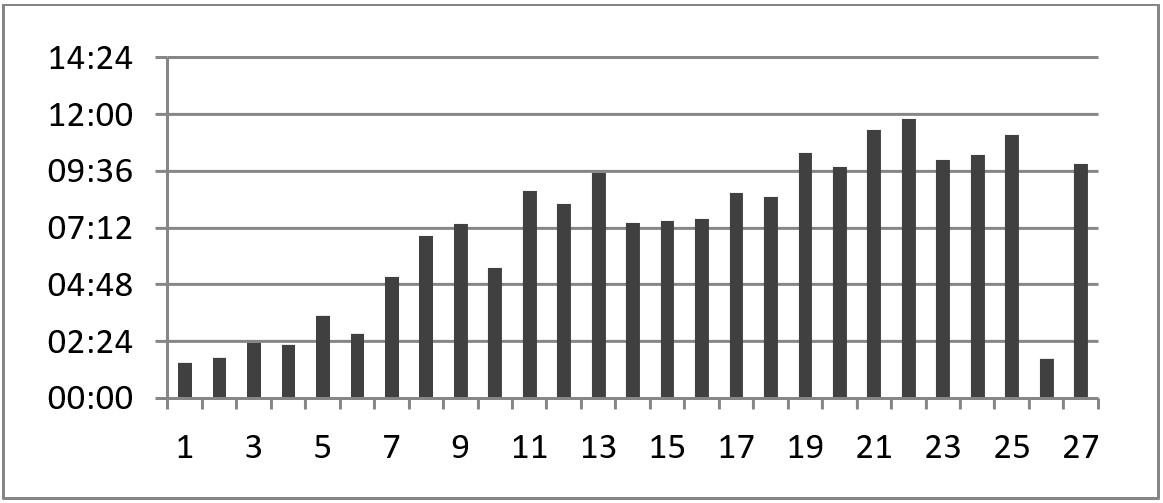

After the second egg was laid, both eagles shared incubation, though the female incubated for longer. By day the eggs were only left uncovered for brief periods of a couple of minutes at the most, for the birds to change shift, or to stretch and roll the eggs. The female alone incubated at night, again only leaving the eggs uncovered for really short periods.

In the first 21 days of daytime full incubation after the second egg was laid the female incubated for nearly 146 hours and the male for nearly 96 hours. In the same period last season, the female incubated for 127 hours and the male for over 104 hours. This shows a similar pattern between the 2 seasons.

For the total full incubation period, from lay of the second egg to hatch of the second egg, the female incubated during the day for just over 258 hours and the male for just over 177 hours.

The female took the night shifts, with the eggs only uncovered for brief periods, as she shuffled, stretched and rolled the eggs.

During those daylight hours, between 6:00 and 18:00, the eggs were uncovered for only 18 hours and 49 minutes total. The eggs were only uncovered for mostly short breaks of up to 5 minutes and mostly either adult was either on the nest or nearby. By comparison, egg 1 was uncovered for a similar time during the delayed incubation period of 80 hours, before egg 2 was laid.

Both eagles brought leaves and the odd stick in to furnish the nest.

During the incubation period the eggs were only uncovered for a total of nearly 19 hours

Female incubated for just over 258 hours

Male incubated for just over 177 hours.

Prey provisioning during incubation:

The male brought 20 prey items to the nest, mainly fish and a few birds. The female only brought 2 items. Both would have caught prey and fed off the nest.

Nestling stage:

SE27 hatched just over 32 hours from the observation of pipping and SE28 around 35 hours from pipping. The eggs hatched some 49 hours apart after being laid around 80 hours apart.

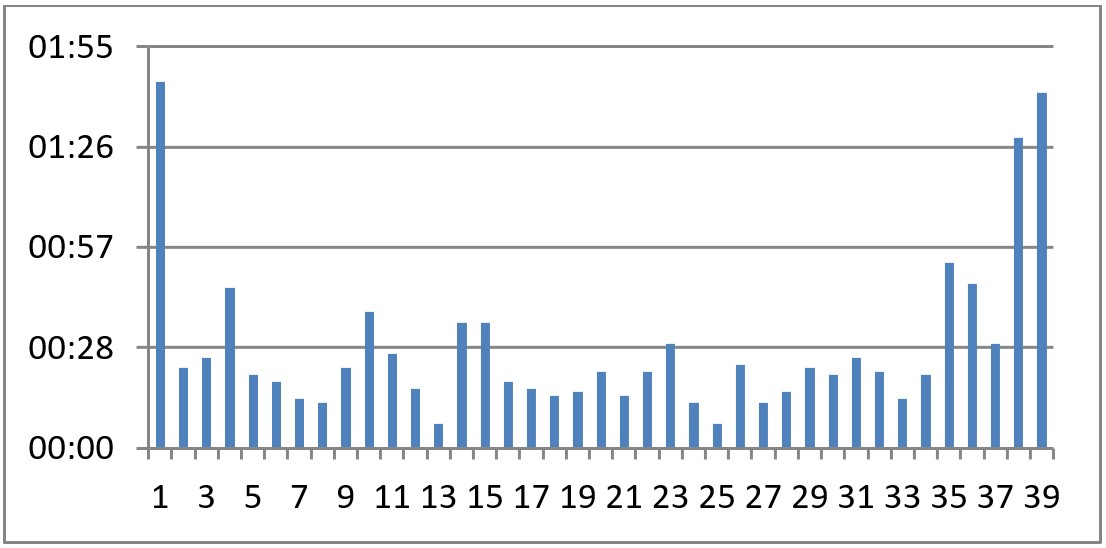

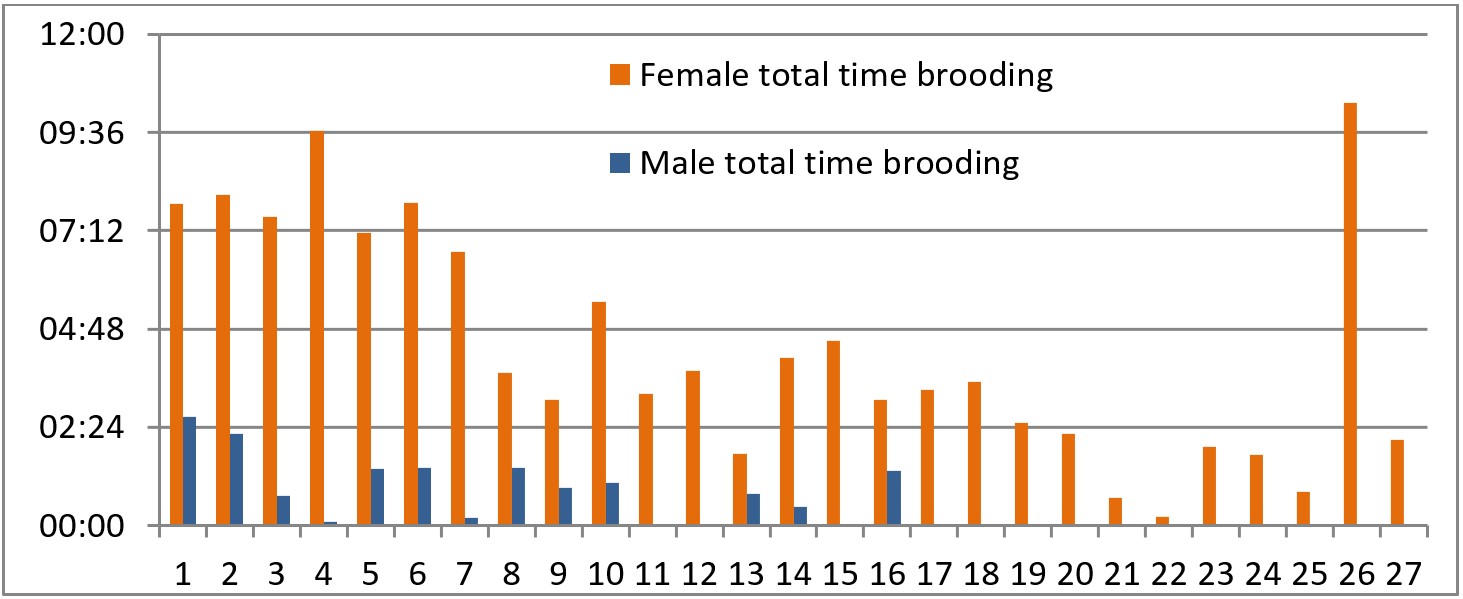

Both eagles shared daytime brood duty, though the female was in attendance for longer and she alone brooded the nestlings at night.

During the daytime initially the chicks were brooded for long periods, as would be expected on cold winter days. As the chicks grew, the brooding time decreased and the chicks were gradually left alone on the nest for longer periods. At about 4 weeks from hatch, they were left uncovered for almost all day, although one or other of the adult eagles was nearby or on the nest. Then on a very wet day the female covered the chicks, sheltering them from the rain for almost the whole day. She also brooded them at that time on those wet nights, when previously the chicks had begun to be only guarded at night.

During this period, the female brooded for nearly 115 hours total by day and the male for a total of only 14.5 hours.

Day 26 was very wet all day.

During this period, the nestlings were not brooded for a total of just over 190 hours

Day 26 was very wet all day, so the female covered them nearly all day.

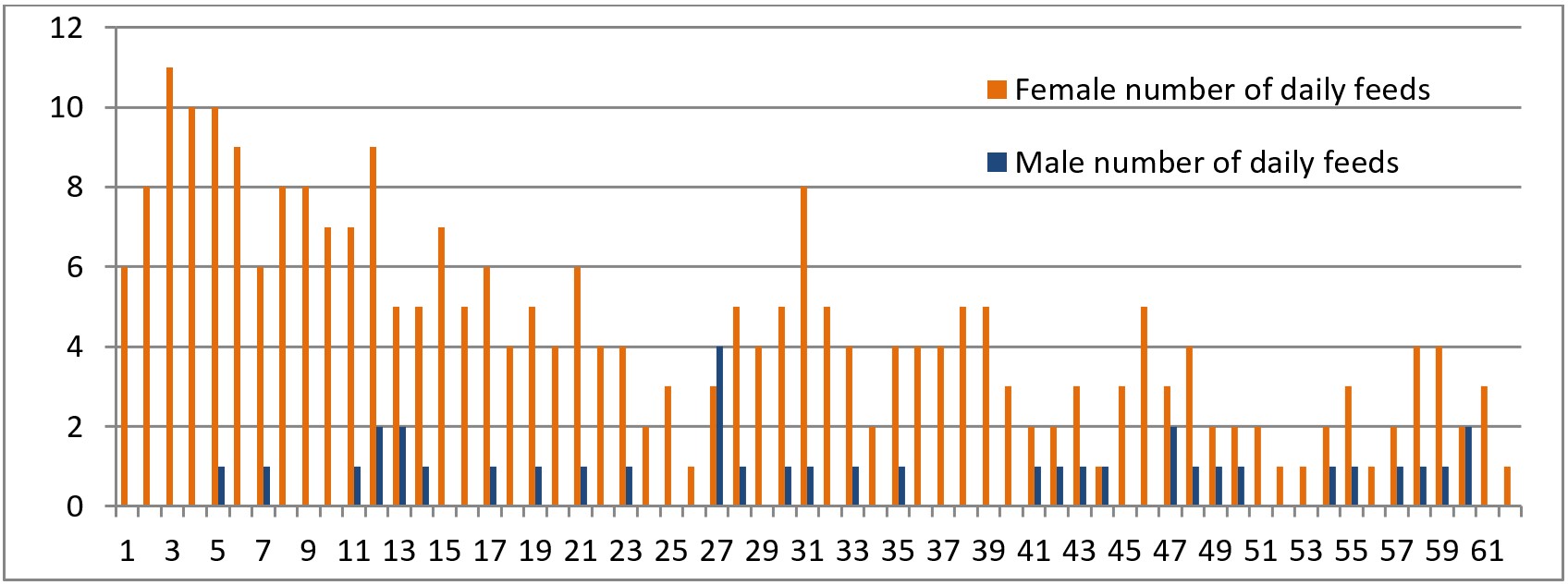

Feeding during nestling stage:

SE-27 received its first tiny feed on the first day, after hatching the evening before.

SE-28 hatched around 49 hours later and received its first feed the next day.

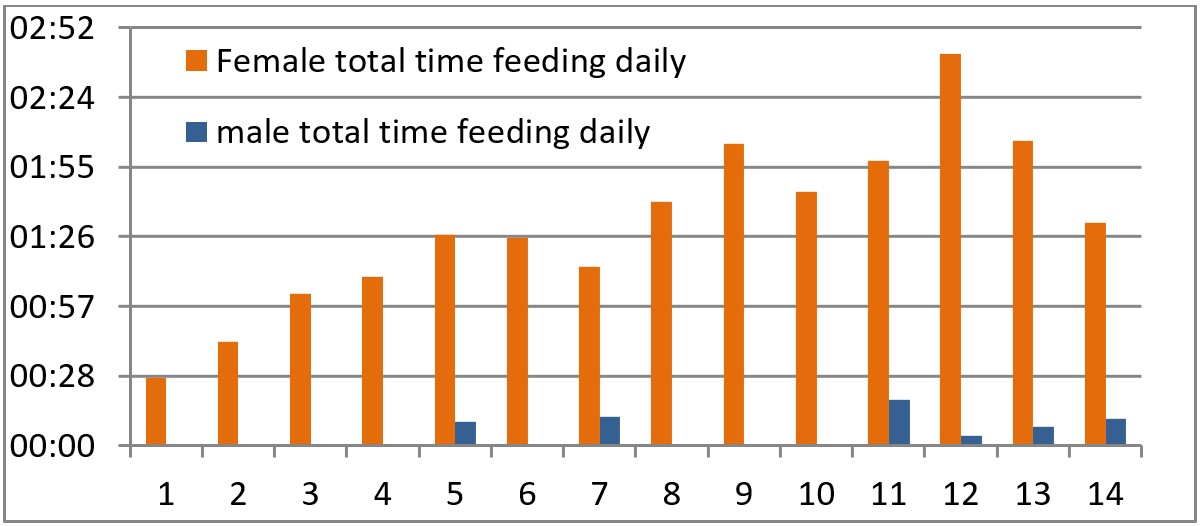

During the first 2 weeks, the female fed the chicks more often than the male, with 109 feeding sessions, totalling 21 hours and 20 minutes. The male fed 8 times, for a total of 42 minutes.

The male was the main provider though in those weeks, bringing 25 prey items, while the female brought 5.

Prey the male brought included: bream, catfish, yellowtail, mullet, whiting and a few nestlings.

As the nestlings grew, they were fed less frequently, with the female continuing to feed the nestlings more frequently than the male.

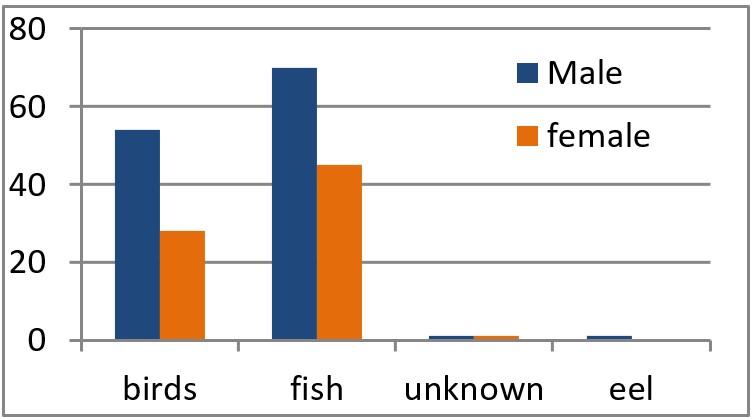

Prey provisioning during Nestling stage:

During those 62 days, the male brought 126 prey items to the nest and the female brought 74.

| - | Birds | Fish | Unknown | Eel | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 54 | 70 | 1 | 1 | 126 |

| Female | 28 | 45 | 1 | - | 74 |

| Total | 82 | 115 | 2 | 1 | 200 |

A variety of prey was brought to the nestlings, including Silver Gull nestlings. The eagles found nesting Silver Gulls in Homebush Bay and were bringing in nestlings as well as some older gulls. They were often escorted in by screaming gulls.

| - | Birds | Fish | Unknown | Eel | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 58 | 77 | 1 | 1 | 137 |

| Female | 35 | 56 | 1 | - | 102 |

| Total | 93 | 133 | 2 | 1 | 239 |

Birds included Silver Gull, Pigeons and Australian White Ibis Chick.

Fish species included Sand Whiting, Bream, Yellowtail, Eel-tailed Catfish, Leatherjacket, Mulloway, Mullet and Eel.

Sibling rivalry:

By about 4 weeks, the eaglets were both growing strongly, developing pin feathers and spending more time alone on the nest. Delayed incubation of the first egg gave the second a significant chance to catch up. However the first hatched chick will nearly always be bigger and stronger in the first important weeks as a nestling. In some raptor species it is common to see rivalry between the nestlings, with the older chick usually the more dominant. The stronger chick may dominate the food supply, pecking at the weaker to prevent it from eating. In extreme cases it may even kill the weaker.

We observed little sibling rivalry in the first couple of weeks.

At 25 days from hatch, SE27 showed quite aggressive behaviour towards its smaller sibling SE28, pecking it whenever it tried to be fed. SE28’s reaction was to turn away, in a submissive posture. This reduced the aggressive behaviour but prevented it from receiving food.

Food supplied may have been less, though fish were being brought to the nest.

This sibling rivalry is normal behaviour in many raptors. It may be seen when food is scarce. Neither adult eagle will intervene to prevent this aggression. Maybe a strategy for survival of the fittest nestling?

Live streaming was turned off during this period of aggression. After a few days, the live streaming was resumed when the aggression lessened. Both nestlings were then fed equally, though SE28 still cowered at times, before receiving food.

Nestling Growth:

At this stage, after the rivalry stage around week 4, dark pin feathers were showing and both were growing fast. At night the female was mostly sitting on the edge of the nest or on a nearby branch – as the chicks were too big to brood now.

By around 6 weeks from hatch, both nestlings were well coloured with their brown feathers coming in. Both were mantling over prey and self-feeding. Both were exercising and flapping their wings, but still sheltering under Lady on a wet night - though there was not much room.

As the nestlings grew, they were self-feeding and mantling over prey. Often bird prey was plucked away from the nest, and the carcass brought to the nestlings.

By week 9 both were vigorously exercising their developing wings and gaining strength , flapping and jumping on the nest.

The nestlings were now standing to sleep for most of the night.

Branching:

The younger eaglet SE-28 branched at 77 days from hatch, flapping rather awkwardly to a branch above. SE-27 the older nestling branched at 81 days a few days later.

Earlier in the nestling stage, other birds were observed swooping the nest and eagles. In particular as the eagles flew in to the nest, they were frequently chased by Australian Ravens. A Southern Boobook was often seen at the nest at night.

During this later nestling stage, both the eaglets and the adults were relentlessly swooped by Pied Currawongs and Magpies, probably nesting nearby. Swooping currawongs particular harassed the newly fledged eaglets.

Fledging:

Both eaglets fledged on the same day. SE-28 fledged at 83 days, falling from a branch, but appeared to have landed close by. Shortly after, SE-27 also flew off, at 85 days from hatch, perhaps urged by a swooping currawong. Both eaglets self-fed on a gull nestling before they left. After fledging, neither eaglet returned to the nest or was seen with the parents. SE-27 was photographed and identified on the ground, just out of the forest area. It did not seem to have skills for flying to a safer perch yet. The female was seen with prey, flying in circles over the saltmarsh - searching for her young? There were no confirmed sightings of SE-28. The adults returned to the nest with prey but then were seen to take it off again.

On October 27th SE-27 was found on the roadside in a busy area of Sydney Olympic Park. The eaglet was taken for veterinary care and assessment. It may have become "lost" flying away from the wetlands and becoming confused. It was probably dehydrated but received the necessary care and assessment at Taronga Wildlife Hospital. SE-27 was identified as a female, and in care was gaining in strength and feeding by herself. On November 18th SE-27 was released, close to the nest area. She made her way towards the river and last was sighted on the other side of the river. The parents again returned to the nest that evening – but were not seen interacting at all with either fledgling. There were no sightings of either fledgling for some time. The parents were moving between their favourite river roosts and close to Goat Island.

In early December, SE-27 was captured further up the Parramatta River, in the suburbs, and was brought back in for care. The bird was assessed to be weak and dehydrated but with no significant injuries. She remained in care for a few days and was transferred to another facility for further rehabilitation. SE-27 had been banded on her left leg. She remained in care at Raptor Care Australia, gaining strength and hunting skills.

In early April, after veterinary assessment, SE-27 was fitted with tail-mounted solar-powered satellite tracker by the team at Australian Raptor Care and Conservation Inc. as part of their Scientific Research Program. After a few days with a Raptor Carer in the Yarramalong Valley, she was released back into the wild in Ku-ring-gai National Park. This area was discussed and approved by NPWS as an area with less disturbance and where other juvenile Sea-Eagles are seen. She flew off very strongly, perching in a nearby tree before flying off. From tracker reports, SE-27 was reported flying northwards. Her dispersal flight has been followed by ARCC Inc. and a report will be published .

There have been no confirmed sightings of SE-28.

Acknowledgements:

The EagleCAM research project team acknowledges the assistance of National Parks & Wildlife Service and Sydney Olympic Park Authority in approving this research and facilitating access to the Nature Reserve and other facilities.

We acknowledge the essential assistance from the EagleCAM team:

Camera installation, electrics, cabling and maintenance: Judy Harrington, Geoff Hutchinson, Bob Oomen and Chris Bruce

Daily Operations & Socials: Shirley McGregor

Minnit Chat: Helen Stibbs

Research Notetakers: Dasha, Cathy, Kathryn, Pat and Helen

Camera Operations: Dasha, Cathy and Helen

Additionally, we also have a wonderful team of volunteers including Facebook admins, chat moderators, ground observers and more (too many to mention here). Above all, thank you to our Supporters, for funding this project.