BirdLife Southern NSW, EagleCAM research team Judy Harrington, Geoff Hutchinson, Jon Irvine.

Summary :

In the 2019 breeding season, the resident pair of White-bellied Sea-Eagles nested in the Nature Reserve forest, and 2 eggs were laid. The study again revealed delayed incubation between the laying of the two eggs. Both young eagles survived to fledge. The second eaglet hatched, SE-24, fledged at 77 days, before its older sibling and survived to be seen hunting on the Parramatta River and has probably dispersed. The older eaglet SE-23 fledged at 82 days but was found dead in its natal territory at 103 days. In the period of this continuing study, the breeding success has been 45.5%, with an average of around one juvenile successfully fledged each season.

Introduction :

There has been a Sea-Eagle nest in the Newington Nature Reserve at Sydney Olympic Park by the Parramatta River for many years, with a succession of eagle pairs renovating a nest in the breeding season. There are few early records of successful breeding however and several eagles were found dead in 2004. Following the death of a pair of breeding eagles in 2004, necropsy and chemical analysis of tissues was undertaken in order to determine the cause of death.

Roach A (2008) PBDEs in Sediment Fish & WBSE Sydney Harbour.pdf )

Further study was recommended. Their success or failure appears to be closely linked with environmental conditions, particularly the accumulated Persistent Organic Pesticides in Homebush Bay and the Parramatta River. Nesting failure has been caused by infertile eggs, sibling rivalry, Beak and Feather Disease, or Trichomoniasis (see previous reports for more detail).

As in previous years since 2009, the breeding relationships, behaviour and diet of the White-bellied Sea-Eagles were studied using CCTV cameras and by limited physical observation during daylight hours, from the time of nest renovation to fledging and beyond where possible. In early 2019 a new Research Proposal was submitted and all approvals gained.

The Sea-Eagle is listed in NSW as vulnerable under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and nationally in Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 as Marine and Migratory.

Nest renovation :

Renovation of the previous nest (first constructed 2014) continued from April, with both eagles bringing sticks and fresh leaves to renovate the nest. The male brought prey items to the nest and mating near the nest was recorded. Duetting was commonly observed, reinforcing their bond.

Delayed Incubation 2019 :

The eggs were laid some 73 hours apart.

Egg 1 SE-23 was laid at 17:37 on June 16.

The second egg SE-24 was laid at 18:43, on June 19.

The first night after egg 1 was laid, when the weather was cold, the female incubated for only 5 hours, leaving the egg uncovered for 5.5 hours. As usually it is the female incubating at night, it was unusual to see that the male incubated for over 2 hours, after 3:00am, possibly due to disturbance nearby.

The next day, both shared daytime egg duty, with the egg uncovered for over 4 hours.

On the second night she again left the egg uncovered, for nearly 6 hours.

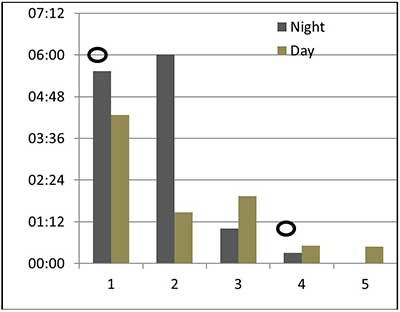

Graph 1 :

Graph 1 :

Number of hours the first egg was uncovered during Incubation before laying of egg 2.

Egg 1 was uncovered nearly 13 hours total at night and nearly 9 hours by day before egg 2 was laid.

Daytime incubation and care at the nest was again shared by both adults. As lay of the second egg approached, incubation time increased until the second egg was laid . Full incubation then continued, with the female on at night, assisted by the male during the day.

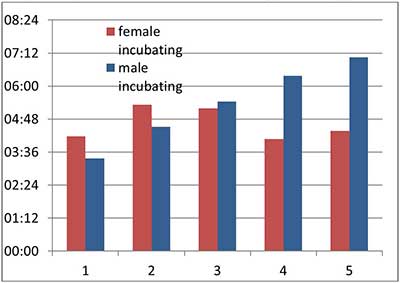

Graph 2 :

Graph 2 :

Daytime Incubation between egg 1 and egg 2.

During the day, both adults incubated, with the female a total of 23 hours and the male nearly 27 hours.

During incubation, the male brought prey to the nest, though not every day. The female brought food a few times, though both probably caught and ate prey elsewhere. Prey brought during this time was mainly fish.

Hatching :

The first chick SE-23 hatched on July 26, after 40 days incubation.

The second chick SE-24 was first seen early in the morning, on the 39th day from lay. Earlier hatching progress overnight was hidden, as the female brooded in the cold. The two eggs were laid around 73 hours apart and hatched about 33 hours apart, after delayed incubation of the first egg.

Nestling stage :

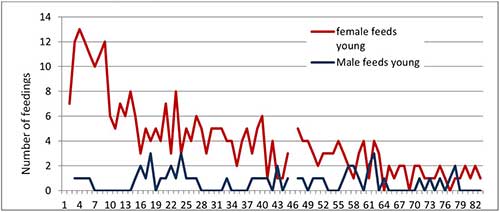

SE-23 received food from the female on the first day after hatching, taking small morsels of whiting from the female’s beak. Initially the female mainly fed the chicks at the nest, with the male contributing more as the chicks progressed. The number of feedings lessened, as the chicks grew and were able to self-feed at the nest with prey the parents brought.

Graph 3 :

Graph 3 :

Daily Feeding Activity at the nest after hatch.

Days since hatch.

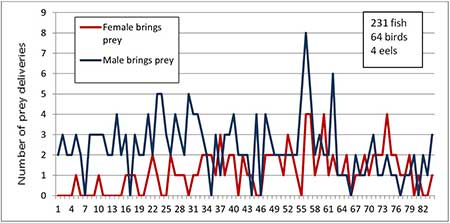

Graph 4 :

Graph 4 :

Daily Prey Delivery at the nest after hatch until fledge.

Days since hatch.

Initially the male brought most prey to the nest, with the female contributing more as the breeding progressed. The prey was mostly fish or birds. Fish included Bream, Whiting and Leatherjacket and birds- pigeons and Silver Gulls. A few eels were delivered as well as left-overs from previous deliveries.

Bird prey was often plucked at the nest. Silver Gulls were commoner later in the season.

Sibling Rivalry :

Though there was delayed incubation, allowing some “catch up” between the two chicks, there was some initial competition from the bigger, first- laid chick SE23. At times the smaller chick SE-24 was submissive and was only fed when the other was satisfied. An interesting observation was when the male brought a bird, possibly pigeon, to the nest on one occasion. He plucked the bird and this bloody prey seemed to stimulate aggression in the bigger chick, SE-23. It picked and pulled at the head of its sibling, removing chunks of fluff. A report on nesting Bald Eagles commented that red, bloody prey seemed to stimulate aggression in the nest. The normal prey, as for these Sea-Eagles, was fish. As the season progressed, this competition decreased. The sibling rivalry did not continue as in the previous year 2018, when competition caused the death of the smaller chick from lack of food. Both eaglets gradually began to self-feed, mantling over prey and eventually feeding themselves from prey brought to the nest by the parents.

Fledging :

As in the past years, as the eaglets grew and developed, they exercised their growing wings, jumping and flapping in the nest bowl. SE-24 branched at just over 10 weeks, flapping to a branch above the nest and then back to the bowl. It was surprising to see that the younger eaglet SE-24 branched before its sibling and then fledged a few days later at 77 days, taking its first flight away from the nest, before returning safely some time later. SE-23 fledged 3 days after the younger, at 82 days from hatch. At the time there was an aggressive magpie near the nest, which swooped the eaglets on the nest. SE-24, newly fledged, was knocked by the magpie and fell to the ground. A circling fox was seen as the camera was focussed on the fallen eaglet, which defended itself with out-stretched wings. Fortunately the fox was scared off and the eaglet flapped to safety in a low tree. After fledging, the adults initially brought prey to the nest, or fed the young birds elsewhere in the forest. The eaglets were eventually no longer seen on the nest. SE-24 was seen by observers in mangroves on the Parramatta River, the favourite river roost of the adults. It was seen taking prey from the adults and flying strongly over the following weeks.

SE-23 was harder to find, though she was photographed on the ground in the casuarinas forest a week or so after fledging. Several days later she was found again on the railway track near the nest. She was seen to fly strongly back into the forest. However, no definite observations were made again of SE-23 and she was found dead on the disused rail track at 103 days.

The dead eaglet was taken to the Taronga Wildlife Hospital for necropsy, which revealed she was emaciated, the muscle mass was reduced and there were no visible fat deposits. The Pathology Report summarised “Based on the bird's very poor body condition and the presence of abnormal ingesta in the ventriculus it seems likely that the animal failed to thrive once fledged”.

This on-going project contributes to knowledge about and protection of this Vulnerable species. The project also satisfies activities suggested by the Office of Heritage and Environment to protect the White-bellied Sea-Eagle:

• Protect known populations and areas of potential habitat from clearing, fragmentation or disturbance.

• Establish 'buffer zones' around nest sites to limit disturbance by humans or human activity. Where nests are located in extensive undisturbed bushland a minimum buffer distance of 500m should be maintained. Where nests are located closer to existing developments a minimum buffer distance of 250m should be maintained, along with an undisturbed corridor at least 100m wide extending from the nest to the nearest foraging grounds.

• Conduct annual, broad surveys to monitor known nest sites, locate new nest sites, determine breeding success and trends in populations, and determine areas of critical habitat.

• Educate the public about the sea-eagle and its status, promote the conservation of the species, and encourage members of the public to report sightings of sea-eagles to the appropriate authorities.

Acknowledgements :

The EagleCAM research project team acknowledges the assistance of Sydney Olympic Park Authority in approving this research and facilitating access to the Nature Reserve and other facilities.

We acknowledge the essential assistance from the EagleCAM team, Judy Harrington, Geoff Hutchinson, Bob Oomen and Chris Bruce, for camera installation and maintenance and all things technical and Shirley McGregor for managing the daily operations. Special thanks to Dasha, Marsha and Pat, for monitoring/nesting observations and Dasha & Helen for camera operations. Additionally, we also have a wonderful team of volunteers including Facebook admins, chat moderators, ground observers and more (too many to mention here). Above all, thank you to our Supporters, for funding this project.

Link to the Information about identifying SE-23.