Judy Harrington, Geoff Hutchinson, Jon Irvine, BirdLife Southern NSW.

Summary:

In the 2018 breeding season, the resident pair of White-bellied Sea-Eagles nested in the Nature Reserve forest, and 2 eggs were laid. The study again revealed delayed incubation between the laying of the two eggs. The smaller chick died at just over 4 weeks from hatch, as a result of sibling rivalry, after limited food was brought to the nest for a week. The surviving chick grew to fledge. After an accident when her wing was caught in a branch, she was taken into care and eventually released after successful rehabilitation.

Introduction:

There has been a Sea-Eagle nest in the Newington Nature Reserve at Sydney Olympic Park by the Parramatta River for many years, with a succession of eagle pairs renovating the nest in the breeding season. There are few early records of successful breeding however and several eagles were found dead. Following the death of a pair of breeding eagles in 2004, necropsy and chemical analysis of tissues was undertaken in order to determine the cause of death. Further study was recommended. Their success or failure appears to be closely linked with environmental conditions, particularly the accumulated Persistent Organic Pesticides in Homebush Bay and the Parramatta River.

As in previous years since 2009, the breeding relationships, behaviour and diet of the White-bellied Sea-Eagles were studied using video CCTV cameras and by limited physical observation during daylight hours, from the time of nest renovation to fledging and beyond where possible. In early 2018 a new Research Proposal was submitted and all approvals gained.

The White-bellied Sea-Eagle Haliaeetus leucogaster (Gmelin 1788) is currently listed as a Vulnerable Species in NSW. (Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. Gazetted date: 16 Dec 2016 Profile last updated: 01 Dec 2017).

In the period of this study, the breeding success has been around 50%, with an average of one juvenile successfully fledged each season.

Nest renovation:

Renovation of the previous nest continued from April, with both eagles bringing sticks and fresh leaves to renovate the old nest. The male brought prey items to the nest and mating at or near the nest was recorded. Duetting was commonly observed, establishing their bond.

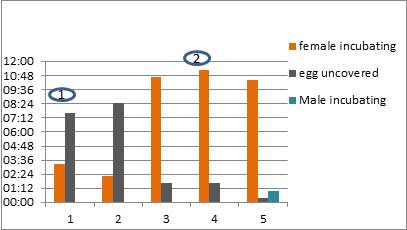

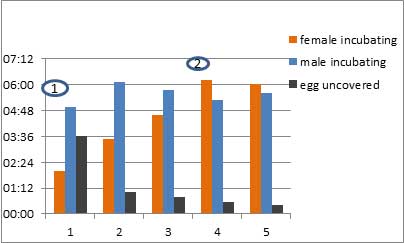

Delayed incubation 2018:

The first egg SE-21 was laid On 11 June 2018, at 5:33pm. During that first cold June night the egg was uncovered for around 7.5 hours, with the female standing on the nest or a branch nearby. The female incubated for a total of only 3 hours and 15 minutes. On the following day the egg was uncovered for just over 3.5 hours. The pair shared incubation duty, the male for 5 hours and the female 2 hours. On the second night, the egg was uncovered even longer for 8.5 hours. By Day 2, incubation time increased and the egg was uncovered for 1 hour total.

This increased incubation on Day 2 indicated that full incubation of the first egg was delayed by some 36 hours from lay, with the egg uncovered for nearly 20 hours total. That night the egg was only uncovered for 1.5 hours, with incubation as usual by the female. On Day 3 the egg was only uncovered for 48 minutes with the pair sharing incubation again.

The second egg SE-22 was laid On the 14 June 2018, at 6:15pm, 73 hours after the first egg. Full incubation continued with the female on the nest all night. The eggs were uncovered only 1.5 hours total, with the female up and down briefly, rolling the eggs and stretching The following day with 2 eggs in the nest both parents incubated almost equally. The eggs were only uncovered for 30 minutes total. That night the female was on nest all night and the eggs uncovered only 20 minutes. However their usual behaviour was altered as the male incubated for 1 hour after disturbance on the nest tree. Daytime and night time full incubation then continued until hatch, with the eggs only briefly uncovered and both sharing incubation.

Hatching:

SE-21 hatched on 21 July 2018 at 3:00pm, taking some 26 hours from pip. This was 40 days from lay, or on the 39th day after delayed or only partial incubation of the first egg for some 36 hours from lay, with the egg uncovered for nearly 20 hours total initially during that period.

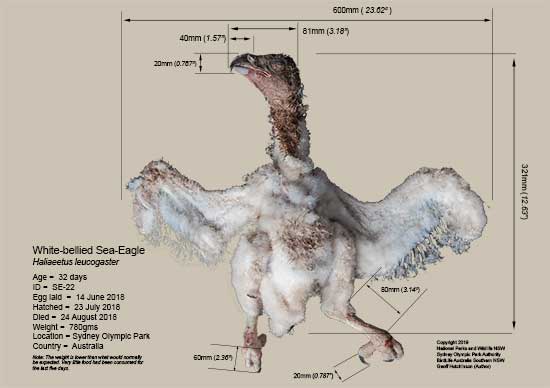

SE-22 hatched on 23 July 2018 at 6:30am. The eggs laid 73 hours apart and hatched 37 hours apart.

Nestling stage:

Although there was delayed incubation, allowing some “catch up” between the two chicks, there was some initial competition from the bigger, first - laid chick SE-21. She initially always received the first feed and pecked at her sibling SE-22 often, causing him to retreat in submission.

This sibling rivalry gradually lessened, and after three weeks, both chicks were thriving and developing as expected.

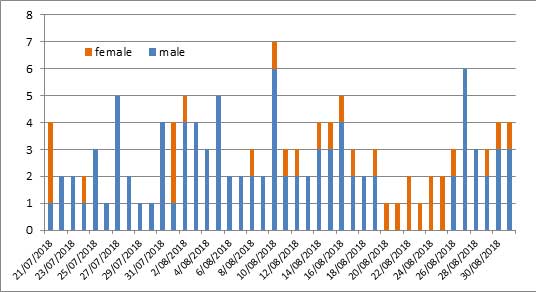

However at about 4 weeks from hatch, there was a period of some 6 days when the Adult male brought no prey to the nest. There had been another juvenile Sea-Eagle seen in the area and the male may have had an altercation with this intruder and possibly been injured. The Adult female brought food each day, but the amount of prey was considerably reduced. With the reduced volume of food the bigger stronger eaglet SE-21 dominated the smaller SE-22, aggression recommenced and for some days SE-22 received no food. SE-22 became gradually weaker and was observed dead on the nest at 33 days from hatch.

The female removed the body after another day and took it away from the nest. The body was retrieved from under a nearby roost and taken to Taronga Wildlife Hospital for examination. In summary, “the bird was very thin and poorly hydrated with no crop or gastrointestinal ingesta. The cranial lesions were consistent with the chick having its head grabbed by the talons of a conspecific”. The emaciation is as we would expect, after many days with no food. After looking at videos of that time, We believe the head injury was caused when the Adult female carried the dead chick from the nest. Some other injuries, to SE-22's feet and head for example, were caused by SE-21 pecking and pulling at her sibling. This sibling rivalry is normal behaviour for some raptors, as happens with many other species in the wild. There were no signs of Trichomoniasis or Beak and Feather Disease in the dead chick SE-22. Pathology Report for SE-22

SE-21, the surviving eaglet, continued to thrive, with ample food brought in. The Adult male apparently recovered and brought prey again shortly after SE-22 died. Both parents then continued to bring food.

SE-21 continued to grow in strength, exercising her wings vigorously and jumping on the nest. Both parents brought food though the male was the main provider.

SE-21 branched at 77 days from hatching. She was also at this stage grabbing prey brought to the nest and self-feeding.

Fledging was on 15 October 2018, at 12:06pm. Week 13.

During October, prey brought to the nest for the young eagle included pigeon. SE-21 was observed with difficulty in swallowing and some gagging with food. Close images of her throat and cere caused concern that she may be suffering from Trichomoniasis, possibly caught from pigeon prey. Trichomoniasis is a disease caused by the protozoan parasite Trichomonas gallinae. Parasites live mainly in the bird’s anterior digestive tract, where they can cause lesions, leading to the death of birds as a result of severe starvation. These images were sent to a number of vets for opinion, including Taronga Wildlife Hospital. They all confirmed that the images were consistent with Trichomoniasis, which can be cured with treatment. However catching the young bird for examination and treatment would be difficult.

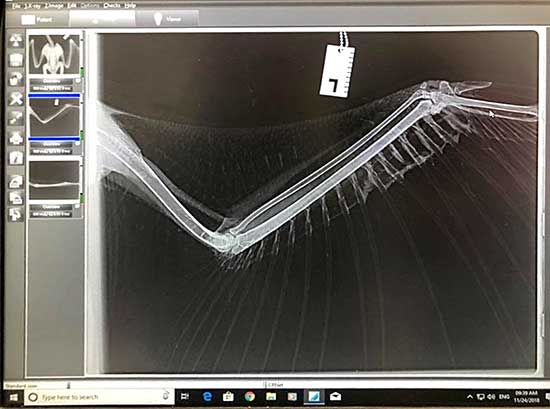

At just on 18 weeks, on a windy night, SE-21 was observed trapped in a branch below the nest, suspended by one wing. Although our Policy is normally for non-intervention, after consultation and gaining approvals, a rescue team entered the forest. The trapped eagle was caught and transported to care by a team from 'Feathered Friends'.

The injured bird received Veterinary care for extensive tissue damage on her wing, as well as for the suspected Trichomonas infection.

Her health and strength improved in care and when stable she was transferred for rehabilitation at Higher Grounds Raptor Centre.

She was released near her nest area at 35 weeks from hatch. The juvenile flew off strongly and was followed in the area for some time. Her current location is not known.

After several weeks of care and veterinary treatment, at the end of March, permission was received from NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service to release SE-21. Although approval had been received for attaching bands, or possibly a tracking device, this was not possible. “....there has been interest in fitting a tracking device and banding SE-21 prior to its release. Advice received by NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) is that minimum intervention is required to best ensure the greatest opportunity for survival of this bird SE-21. Therefore, NPWS did not support these devices being fitted to SE-21”.

In early 2019, the cameras were removed for routine maintenance and a new camera installed at the site known as Ironbark roost nearby. Cameras are now installed above the nest, in a nearby tree and at Ironbark roost.

This on-going project contributes to knowledge about and protection of this Vulnerable species. The project also satisfies activities suggested by the Office of Heritage and Environment to protect the White-bellied Sea-Eagle:

• Protect known populations and areas of potential habitat from clearing, fragmentation or disturbance.

• Establish 'buffer zones' around nest sites to limit disturbance by humans or human activity. Where nests are located in extensive undisturbed bushland a minimum buffer distance of 500m should be maintained. Where nests are located closer to existing developments a minimum buffer distance of 250m should be maintained, along with an undisturbed corridor at least 100m wide extending from the nest to the nearest foraging grounds.

• Conduct annual, broad surveys to monitor known nest sites, locate new nest sites, determine breeding success and trends in populations, and determine areas of critical habitat.

• Educate the public about the sea-eagle and its status, promote the conservation of the species, and encourage members of the public to report sightings of sea-eagles to the appropriate authorities.

www.environment.nsw.gov.au/threatenedspeciesapp/profile.aspx?id=20322